European Pillar of Social Rights: Old Wine in New Bottles?

Politically, the European Pillar of Social Rights (EPSR) reaffirmed social and labour law’s place squarely on the EU agenda. It also raised some hopes for convergence towards higher pan-European legal standards. However, when we look specifically at workers’ rights, we see that hardly anything new has been proposed.

For the most part, the EPSR merely reiterates rights that have already long existed in the EU acquis. Prime examples of this are the right to equal pay for women and men, the right to equal treatment in employment, and the right to be informed and consulted in cases of business transfer, restructuring and mergers. There are very few new rights proclaimed in the EPSR. The most promising, and most frequently mentioned, is the right to fair wages (see also Chapter 4 of Benchmarking Working Europe 2018). The EPSR also adds a deadline to the existing right to be informed about the terms and conditions of employment: this information should be given at the start of employment, instead of within the first two months, as is currently foreseen in the Written Statement Directive. With respect to dismissals, the EPSR establishes the right to a reasonable notice period and the right to be informed about the reasons for the dismissal. Finally, while the Merger Regulation states that workers have to be informed about the merger, the EPSR add the right to consultation.

Authors: Z. Rasnaca and R. Jagodzinski, ETUI.

Source: Benchmarking Working Europe 2019, ETUI, Brussels, p. 79

In this way, the EPSR to a certain extent complements some of the already existing rights. This, however, has mostly been done to remain aligned with the secondary law proposals that were issued alongside the EPSR proposal (on work–life balance, the revision of the Written Statement Directive, and access to social protection).

The Commission’s proposed revision of the Written Statement Directive already proposes that the information on working conditions should be given to the worker on the first day of their employment (European Commission 2017a: 12). Therefore, the EPSR does no more than implement the Commission’s proposal. Similarly, the Commission’s proposal on work-life balance, in line with Principle #9 of the Pillar, envisages that the right to parental leave should provide flexibility in how this leave will be taken (e.g. part-time, full-time or in flexible forms) (European Commission 2017d: 12). Here, again, it can be argued that the Pillar seeks to implement the Commission’s legislative proposal, rather than vice versa.

Furthermore, the Pillar itself requires specific legislative measures to be adopted in order for its rights to be legally enforceable (Recital 14 of the Pre- amble). In this way the EPSR fails to use the opportunity to strengthen the implementation of workers’ rights embedded in EU secondary law.

What does the EPSR actually mean then for workers’ rights at the EU level? In legal terms at least, nothing much beyond reaffirming the existence of already existing rights. Although to a limited extent it adds to existing rights, a major question mark remains hanging over how they will be enforced, and any meaningful enforcement will require the adoption of further (implementing) measures either at national or EU level, and with all the accompanying legislative struggles. A political commitment to the principles which guide social policy is essential.

Authors: R. Jagodziński and Z. Rasnaća (2019)

Authors: R. Jagodziński and Z. Rasnaća (2019)

New momentum?

It was hoped that the 2017 European Pillar of Social Rights (EPSR) would give some ‘new momentum’ to Social Europe by reviving EU social ambitions. Indeed, every 15 years or so, an ambitious proposal to ‘re-balance’ the EU’s economic dimension with its social one is tabled (Pochet 2017). This, the latest of such proposals, was awaited with particularly high expectations by the stakeholders, including trade unions.

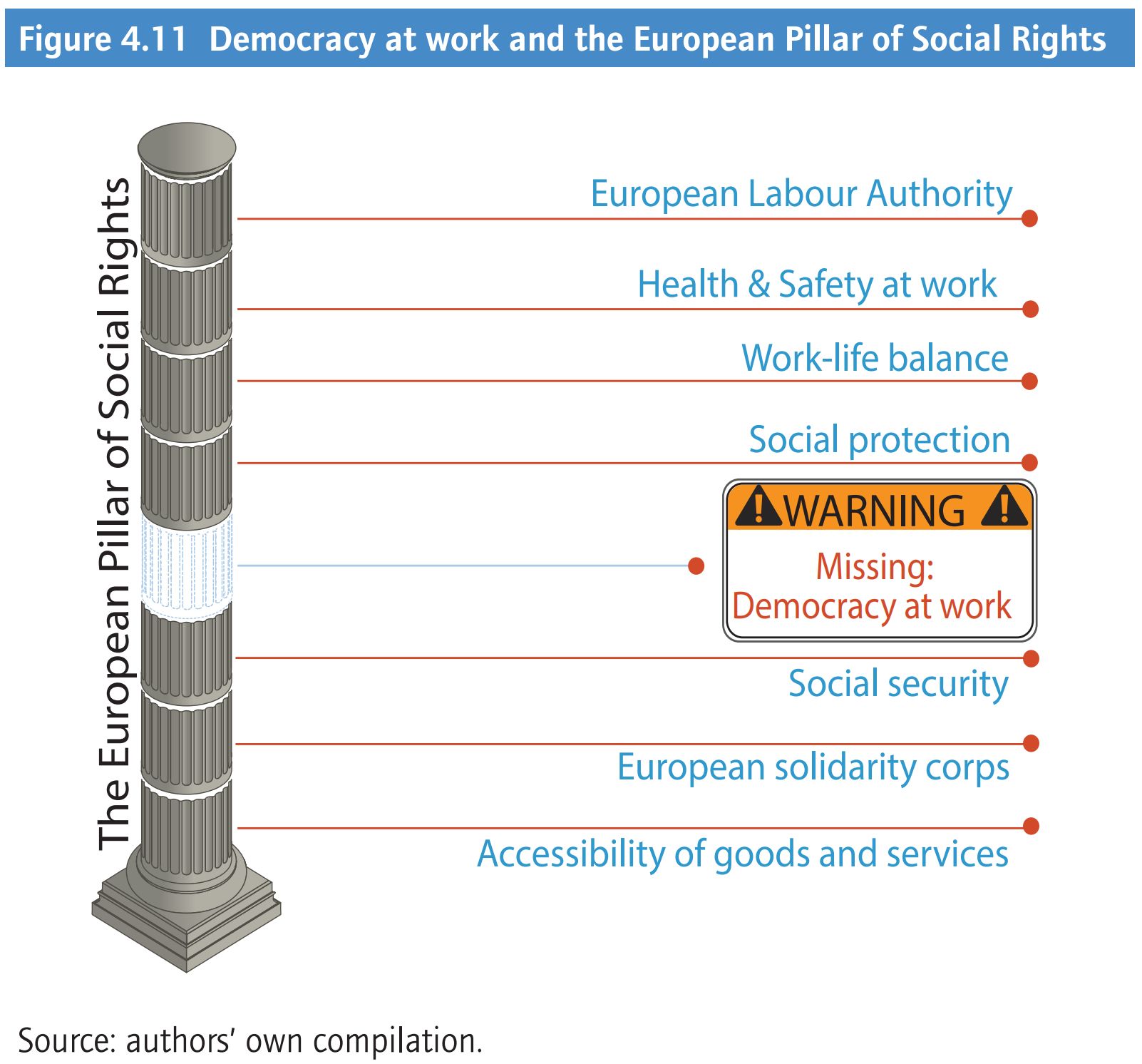

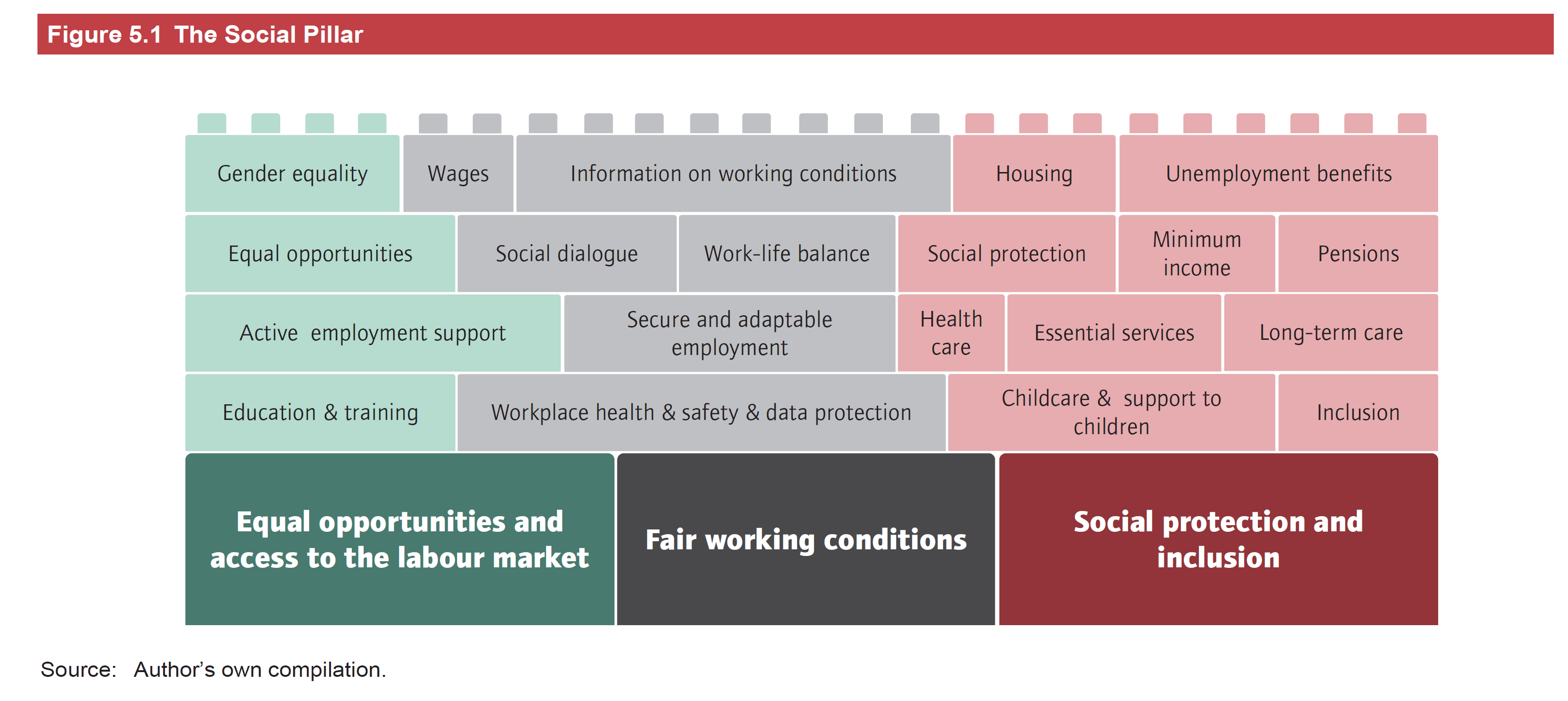

Indeed, the EPSR is the most encompassing social initiative to have been adopted by the EU in the past decade. Its three chapters lay out 20 broad principles in three areas:

1) equal opportunities and access to the labour market;

2) fair working conditions; and 3) social protection and inclusion.

The EPSR not only extends across social policy and labour law, it also seeks to confer new rights – rights previously absent in the EU realm. For example, the EPSR introduces for the first time ‘the right to […] adequate unemployment benefits or reasonable duration’ (#13) and the obligation (for the Member States) to provide adequate shelter and services for the homeless. It also states that everyone lacking sufficient resources has the right to adequate minimum income benefits (#14).

Concerning workers’ rights, the ‘right to fair wages’ is completely new (#6), especially since the EU lacks the legislative competence to regulate pay.

In many ways the EPSR therefore sounds very promising.

However, despite its promise of upward convergence, the EPSR is quite disappointing in terms of its legal form. In fact, the implementation and enforcement of this brand-new instrument raises more questions than answers (Rasnača 2017: 37). The EPSR consists of a recommendation and a proclamation, and both are soft law instruments without legally binding force. The three legislative initiatives issued together with the EPSR (on work–life balance, on the revision of the Written Statement Directive, and on access to social protection) merely make reference to the EPSR rather than set out to implement its principles. Furthermore, despite repeated requests, the Commission has thus far declined to issue a Social Action Plan of future legislative initiatives for implementing the EPSR.

The only area in which the Commission has promised a meaningful role for the EPSR is the European Semester process (European Commission 2017c: 9). Until very recently, however, the country-specific recommendations failed to reflect this promise (Clauwaert 2017: 16). The Social Scoreboard’s set of indicators for monitoring the 20 EPSR principles (ETUI, Scoreboard: 7) have also only very recently been defined (see also Chapters 2 and 3). Therefore, for now the prospects of meaningful implementation and enforcement of the EPSR seem bleak.

At the same time, there are various ways in which the EPSR could be used to strengthen the EU’s social dimension in a significant way.

First, a strong (political) commitment to its implementation and enforcement is needed, together with a concrete action plan, be it from Member States at the national level or from the EU legislator.

Second, independently of political will or the lack thereof, the EPSR could acquire some role in future litigation before the CJEU, perhaps similar to that played by comparable instruments in the past (Rasnača 2017: 33).

Third, it could serve as a shield against attempts to further deregulate social protection (e.g. via the European Semester or EMU mechanisms).

Finally, the EPSR could be used to reach a consensus on at least a few of its principles (such as unemployment insurance) that are essential for the smooth functioning of the EMU (Rasnača and Theodoropoulou 2017: 1). Conceivably, a legally binding framework could be built around such a consensus.